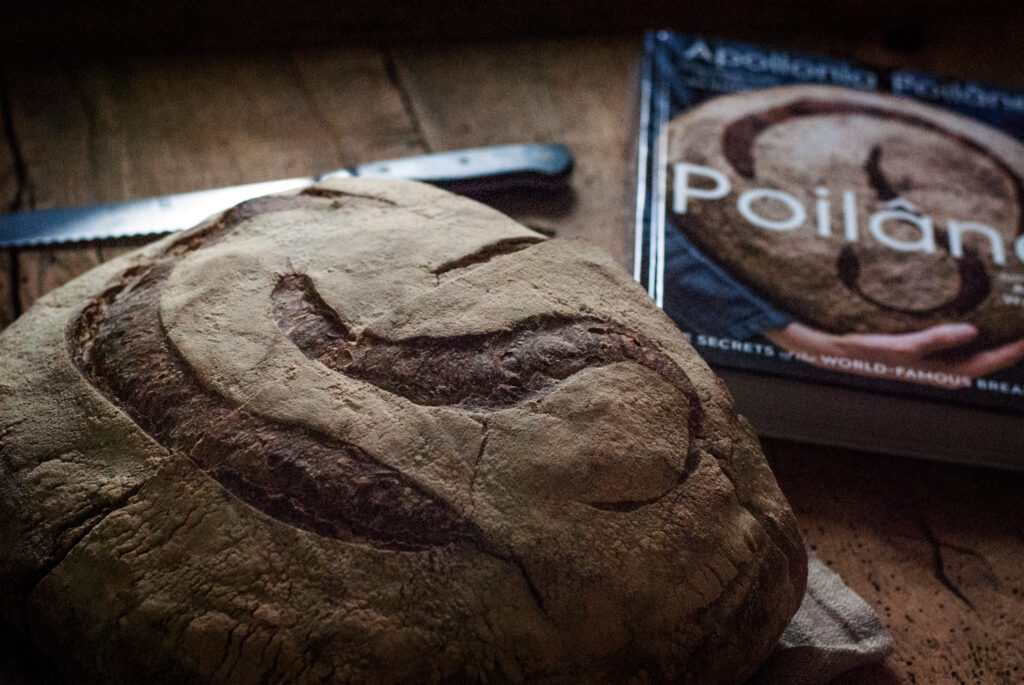

Pan Poilâne

There are few things in life more comforting, more universally appreciated and appealing than a loaf of bread. It exists in every culture– and ironically, no matter what form it takes, its presence on the table denotes family and comfort. The type of bread that you grew up eating is probably still the bread that you serve to your family. Maybe you even buy the same brand, just because it is tied in with your childhood memories. Bread is tradition. Bread is family. Bread is home.

This is the story of one very special bread.

At a deceptively unassuming little bakery at 8 rue du Cherche Midi, in Paris, windows gleam with large, flour-dusted loaves, all inscribed with the letter “P,” cut into each loaf by a master baker prior to firing. The boules are always stacked with the flourished “P” facing up. It is a gesture of respect for the baker. The loaves are little pieces of living history– the bakery uses the same sourdough starter and wood fired oven that it began with in the 1930s. Each time new bread is baked, a bathtub-sized container of raw dough is saved for use in tomorrow’s batches. It has been that way for almost a century. The same starter is still going strong, imparting a unique, literal taste of the past to the tables of the present.

The same oven roars at a constant 500 degrees, blackening the ceiling with soot and completely heating the upstairs store in winter, without the use of external heat. The bakers wear shorts and T shirts as they work. It is close to 80 degrees in the baking room even during the coldest days of winter. It smells like heaven. The loaves crackle and chuckle when they come out of the oven to cool. If you listen carefully you can hear their melody– the dark brown crusts creating a symphony of sound and scent, sighs and steam.

The bakery was founded in 1932 by Pierre Poilâne, the grandfather of its current owner Apollonia. At that time, even more so than it is today, baking bread was backbreaking, thankless work that started in the wee hours of the morning. Pierre would start the fires under his ovens while it was still dark and quiet outside, stoking the coals and stripping down to just a white T shirt and shorts as the heat crested 100+ degrees. Each day he started the grueling task of mixing and kneading the dough by hand, before hefting multiple baskets of it closer to the heat to proof. Sometimes the proofing baskets would be stacked higher than Pierre was tall.

Pierre loved to bake. He loved the smell that emerged as his paddle, as long as the oar of a boat, reached into the smoky depths of the oven to retrieve the perfect, flame-kissed loaves. He listened to the bread crackle quietly, like laughter, as it cooled. He thumped each one soundly on the bottom, listening for the characteristic “door knocking” echo of a bread which was perfectly done in the center. He never cut into the bread warm. His self control ensured that the center of the loaves could finish baking, undisturbed, without becoming gummy.

Pierre was a visionary. Instead of focusing on the classic baguette, as did scores of other boulangeries in the neighborhood, he decided to delve into the history of French breadmaking– to bring back the almost forgotten art of the sourdough boule, a rustic, round loaf which was favored by French peasants as early as Medieval times because it kept for over a week instead of going stale after only a single day. The very rich were the only ones who could afford to separate the germ from the wheat when they made bread, meaning that expensive white bread usually graced the tables of fine homes. But Pierre wanted to bake bread that was brown– the bread of the poor. The bread of the common people. The bread upon which France was built. He wanted to bring it back.

When Pierre first re-introduced the crackly, brown sourdough loaf, no one was sure if he would be successful. After all– this was Paris– the food capital of the world. Was there a place for such humble bread here? Time would tell. Pierre believed in the idea– believed in the product, and soon he was placing his now iconic round loaves into the window of his shop. Loaves of bread are generally slashed with a razor blade (called a “lame”) before baking, so that they don’t get a hollow center. Pierre chose to carve a letter “P” into his loaves– a play on the letters in his last name, Poilâne, and the French word for bread (“le pain”).

People were curious immediately. You could not help but notice the gigantic “P” emblazoned circles as you passed the shop, the scent of freshly baked bread wafting tantalizingly out onto the streets. The loaves were huge (almost 5 pounds each), and the neighborhood was poor. Pierre offered to sell bread in quantities of just a slice or two– a practice unheard of in his day and still in use at Poilâne today– to help the poorer members of the neighborhood afford it. He became beloved in the community– both for his product, which was almost indescribable– a bread which was at once crunchy and chewy, with a satisfying nutty taste and a hint of sourness that paired beautifully with a smear of local butter studded with flakes of sea salt– and for his largesse. No one was ever turned away at Poilâne. If someone couldn’t afford to purchase bread, Pierre allowed him or her to trade for it. He always appreciated art, and to this day the original bakery is decorated with paintings, sculptures, and other pieces of art which were created by local artists, literally, for their daily bread.

Pierre’s son, Lionel, had always wanted to be an artist. One must wonder whether the father’s love of art (so great that he was willing to trade his product for it) had been hereditary. Lionel never wanted to take over his father’s bakery– he felt that the gruelingly early hours and backbreaking labor of the morning ovens and dough preparation was more akin to being punished in a fiery inferno than having a career. Unfortunately, when Lionel was only 28 years old his father suffered a stroke– and Lionel had to step in as the bakery’s manager to keep the business going. Lionel described himself at the time as “A very bitter boy stuck down in the basement.” He grudgingly fulfilled the bakery’s obligations, dreaming about a very different life. The only time he smiled was when he flew through the dark morning streets to work on his in-line skates, feeling as if, for the briefest of moments, he truly could fly.

But often life has a way of turning things around when we least expect it. Lionel discovered that he was good at the bakery business– a surprise coming from the boy who had wanted to live exclusively for creative pursuits. He began reaching out to celebrity chefs and food historians, telling them about his product– about its unerring attention to detail and respect for the way historical breads were made. He told about the relationships that he had with his product suppliers– that ever since his father’s days someone from the bakery personally visited the farms where their wheat came from and never purchased no name ingredients from a source they didn’t personally know and trust. Lionel even wrote to the pope, petitioning His Holiness to remove “gluttony” from the list of deadly sins. Under his careful management, the once tiny, local business began to blossom from a single bakery to a household name and, some say, the best bread in all of Paris.

Lionel was a natural. With his dapper bow tie and charming French accent, he was the quintessential French baker. When his daughter Apollonia was born, he allowed her to nap in an empty bread basket in his office. From the start, it had been a family business, through and through.

But on the heels of such great success, there followed almost unimaginable tragedy. On Halloween night in 2002, both Lionel and his wife were killed in a helicopter crash off the coast of Brittany when Lionel tried to land their aircraft in heavy fog. Apollonia was only 18 years old at the time– a mere wisp of a girl who was about to attend college. Who would take over the bakery? Surely not this teenager. She was about to go away to America to school. Should she give up college and run the business? Was she even capable, at her young age, of stepping into such powerful shoes, mere days after losing both her parents and assuming custody of her younger sister? It was such a crushingly heavy load for such small shoulders. No one thought she could do it.

But she did.

Apollonia continued with her plans to attended Harvard and managed to run the, by now, world-famous Poilâne bakery from her college dorm room for the 4 years until she graduated (earning a degree in economics). She had new loaves shipped overnight to her for quality checks and made mammoth business decisions while she studied for her freshman exams. It was common for her to plan her schedule around bakery business– she often had to rise in the middle of the night to take a call from Paris, as her bakers on the other side of the world were starting with their day. The veteran bakers were impressed with Apollonia’s humility and drive. She did not step in and run the business into the ground, as many teenagers would have. She truly wanted to learn from them and respected them and the time they had spent learning from her father, or, in some cases, her grandfather. “The one or two hours you spend procrastinating I spend working,” she remarked when someone asked her how she ever expected to succeed. “The work of several generations is at stake.”

Apollonia is a quiet, no-nonsense owner. She is small and thin, with eyes that hold your gaze and look down from no one. She has earned the right to keep her head held high. At the age of 35 she has already been at the helm of a multi-million dollar business for a remarkable 17 years. She has been there since the day after she learned of both her parents’ deaths, when she stalwartly entered the bakery, sat down at her father’s desk, and said she had decided to keep the bakery going, rather than sell it.

She is known as a tough boss– but then again, she has to be. She didn’t allow herself any shortcuts, just because she was the owner. Like she expects of all her workers, Apollonia completed the incredibly demanding and rigorous 9 month apprenticeship alongside one of the master bakers to learn how to make the sourdough boules correctly. No recipes are ever used at Poilâne– rather, the bakers are taught to create the dough based on their senses, the weather, and their expertise of the craft. The dough has only 4 ingredients– stone ground flour, water, the same sourdough starter that Pierre used almost a century ago, and salt (they prefer Fleur de Sel from the salt marshes of Guerande– known as the “caviar of salts,” and known the world over for its incredible purity and taste). The ovens have no temperature gauges. The bakers know when the temperature is right by holding a piece of paper in the opening. If the oven’s fiery breath turns it a specific shade of brown, the bakers know that the heat is just right.

The bakers still make the loaves the same way as Pierre taught the very first employees of Poilâne– each baker follows his loaf from start to finish, taking personal pride in it and marking it with his own “P” as it goes into the oven. Apollonia can instantly tell which baker created each loaf, based on the signature handwriting of the “P” on top. At her request, she receives 24 sourdough boules each day– one from each master baker in her employment. She evaluates each loaf daily. “I just look at the breads and get a sense of the aesthetic of them,” she says. “This way, even if I haven’t had time to go to the manufactory, I can keep track.”

She is an amazing woman. And the product which she creates is remarkable. David Lebovitz, famous Paris food blogger, has said that his first thoughts of moving to Paris were because he wanted to be near Poilâne bakery. The iconic loaves (so large that if you hold your arms in front of you and touch your fingers, you could get an idea of the dimension of them) are now shipped all over the world. The president of France, himself, receives deliveries from Poilâne several times a week. Restaurants advertise when they use the bread, because the very sight of its name is enough to draw in customers.

Apollonia, I think your father and grandfather would be proud.

Much thanks to Lauren Collins of The New Yorker. Her article about the history of Poilâne was invaluable as I researched this bakery.

Also thanks to Apollonia’s new book, Poilâne, which is a beautiful tribute to her family and the bakery which bears her name. I enjoyed it immensely.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which just means that we get a few pennies if you purchase through our link. I never recommend products that I don't personally use and love. Thanks!